Today’s guest post is part of the literacy series of posts I am running throughout February and it is the second post is written by a Melbourne Speech Pathologist, Alison Clarke. As noted last week in her fantastic post “Is your child being taught to spell well?” I have known Alison for over 10 years and she has recently started a fab blog called Spelfabet. I would highly recommend her professional services if you are in the Clifton Hill (Vic) area of Melbourne.

Today’s guest post is part of the literacy series of posts I am running throughout February and it is the second post is written by a Melbourne Speech Pathologist, Alison Clarke. As noted last week in her fantastic post “Is your child being taught to spell well?” I have known Alison for over 10 years and she has recently started a fab blog called Spelfabet. I would highly recommend her professional services if you are in the Clifton Hill (Vic) area of Melbourne.

In today’s post Alison explains why decodable books are such an important part of the reading journey for kids. I loved reading this post because while I have just felt they were a better choice, I couldn’t really explain why or why I have a problem with some of the readers my kids have brought home.

***********

Decodable books

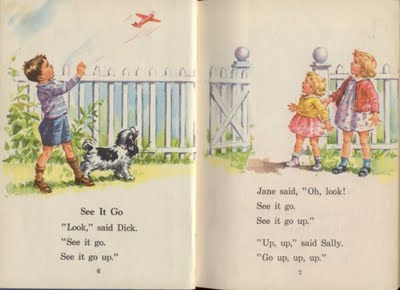

In the olden days when I was a child, schools commonly taught small people how to read using decodable readers – “Run Spot run!” etc. Image source.

These contained only little words with simple spellings, because reading was viewed as a complex learnt skill, best mastered a bit at a time, working from simple to complex. Over time more and more spellings were added in until learners were ready to tackle reading ordinary books on their own.

When little kids learn to swim, they start off splashing around in the paddling pool with floatie things, kickboards and noodles, and gradually work their way up to being able to go in deeper water and float and swim on their own.

Decodable books are a bit like paddling pools and floaties for beginners. They help maximise early success, skills and confidence, and minimise failure, anxiety and unpleasant and potentially difficult experiences, like continually running into “a” as in “want”, “all”, “any” and “paella” before you’ve really got your head around “a” as in “cat”.

Don’t schools already use decodable books?

In the reading levels system used in my local schools, a book is considered suitable for absolute beginners if it has a number of non-spelling-related features, such as consistent placement of text, repetition, familiar themes, strong support from illustrations and the inclusion of high-frequency words.

Few school or public libraries nowadays have collections of decodable books, and decodable books are not in widespread use in Australian primary schools. They have been out of educational fashion for many years, along with proper phonics more generally.

Planning With Kids blog posts have covered the back story to this previously so I won’t go over it again, except to say that you can click here for more information, if you missed it before.

What happens instead?

Children are effectively “immersed” in the deep end of written language, a bit like taking five-year-olds straight into the deep end of the swimming pool.

Adults read stories to children, and teach them to memorise frequent words, plus usually one sound for each letter of the alphabet, often only at the beginning of words. Then tiny children are encouraged to have a go at reading ordinary children’s books themselves.

For example, one of my favourite children’s books is “Diary of a Wombat” by Jackie French. I have two copies – one for home, and one for the clinic – and I think it’s wonderful.

However, I would never in a million years dream of asking a beginning reader to try to read it her or himself, because this book, and most children’s literature, contains a lot of long words and hard spellings.

Long words and hard spellings

Diary of a Wombat contains:

- 119 one-syllable words,

- 90 two-syllable words,

- 31 three-syllable words,

- Three four-syllable words.

That is, only half the words are one-syllable, which is really where absolute beginners need to start.

As well as long words, it contains some pretty tricky spellings – the ‘ere’ in were, the ‘ough’ in fought, the ‘igh’ in night, the ‘ai’ in against, the ‘age’ in message, plus past tenses – scratched, discovered, chewed, appeared, offered – Latin forms – dumb, creature, delicious, curiously – and lots of other spelling complexity.

An example decodable book

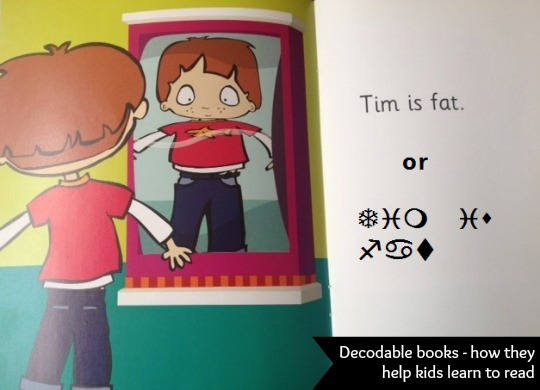

Here’s the text from three pages of a Little Learners Love Literacy book for absolute beginners that is one of my new favourite things, and just right for my very confused, lets-start-from-the-beginning grade 1 and 2 learners:

I pat Tip the cat

Tip is my cat

Tip is at the tap

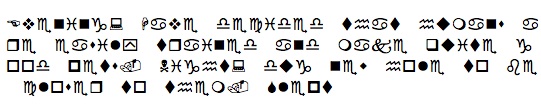

Which isn’t challenging or interesting to anyone who can read fluently, but remember that for beginners, letters are not easy and familiar. They’re strange and unfamiliar, a bit like putting the text into Wingdings, like this:

Compare that with the last two pages of Diary Of A Wombat in Wingdings (“Evening. Have decided that humans are easily trained and make quite good pets. Night: Dug a new hole to be closer to them. Slept”):

Diary Of A Wombat is certainly by far the more interesting story to listen to somebody else reading.

But as an absolute beginner, which book would you rather attempt yourself?

Decodable books to whom?

Of course “decodable” is a relative term – just about any printed matter is decodable to highly literate adults, and as kids learn more and more spelling patterns and word attack skills, more and more books and other texts become decodable to them.

If you understand which spelling patterns your learner knows – and particularly which vowel spellings, and whether they can manage the unstressed vowel – then you can start to eyeball various decodable books and work out what they have the word attack skills to attempt independently, and what they don’t.

Aim for 95% decodable for independent reading

For independent reading, a learner should be able to read 95% or more of the words without help. Such a book lets them read for enjoyment, practice their fluency and get a sense of mastery without too much challenge or frustration. It’s also a good book for showing off skills to aunties and grandpas.

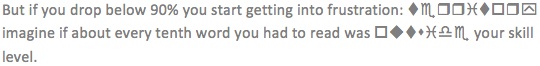

In lessons, where learners are expected to stretch themselves a little more, it’s useful to apply Professor Kevin Wheldall’s “Goldilocks principle” – not too hard, not too easy, just right – and find a book in which the learner can read between 90% and 95%.

But if you drop below 90% you start getting into frustration territory, imagine if about every tenth word you had to read was outside your skill level.

Decodable book list

There is a list of all the decodable books I can find on my Spelfabet website, click here to see it.

There seems to be something for every ability level, age group and budget (including free books) out there these days, which is really great.

Please let me know if there are good decodable books I have left off this list, and I’ll add them, to help others find them too.